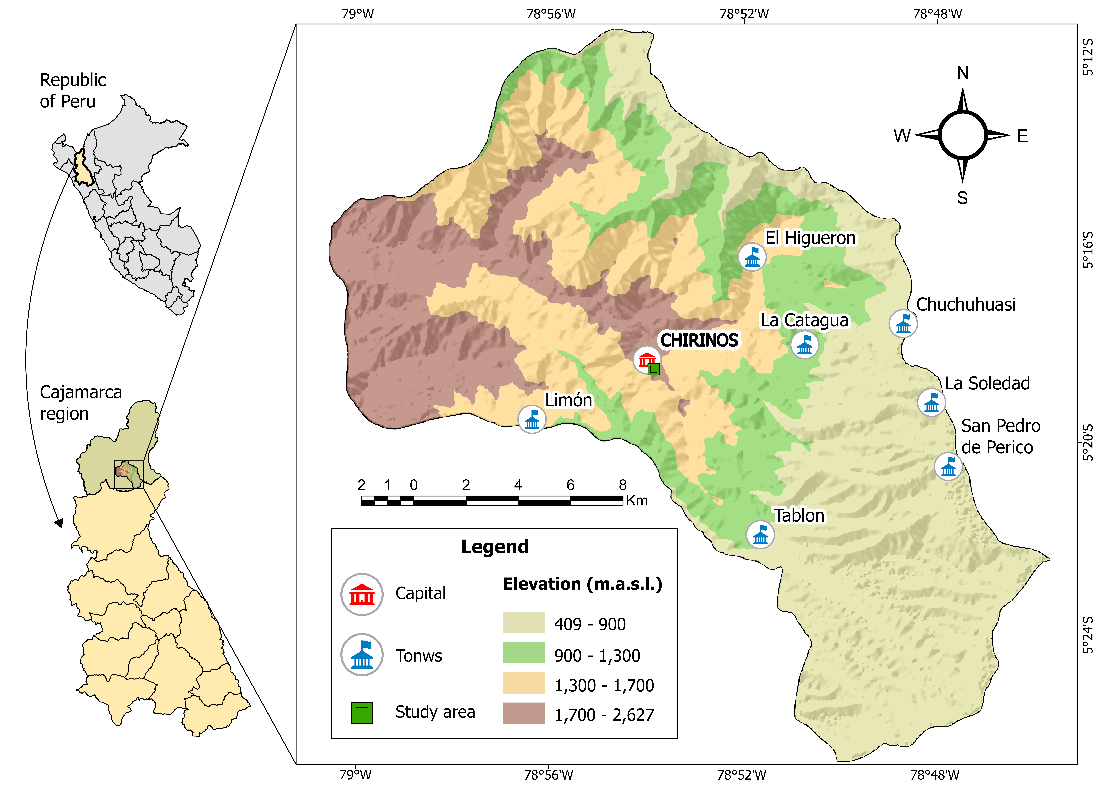

Estimation of diurnal greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from unfertilized coffee soils using recurrent neural networks (RNN). A case study for Chirinos, San Ignacio Province, Cajamarca, Peru

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.18686/cest544Keywords:

Climate change , Gases , Soil , Air pollution , Artificial intelligence , climate change; gases; soil; air pollution; artificial intelligenceAbstract

Global warming, driven by rising greenhouse gas (GHG) concentrations, has agriculture as a major source of emissions. In coffee plantations, low sampling frequency and the absence of diurnal baselines introduce bias in emission estimates. The objective of this research was to estimate diurnal CO₂, N₂O, and CH₄ emissions from unfertilized coffee soils using recurrent neural networks (RNN). Gas fluxes were measured with a closed dynamic chamber (CDC) at 20-minute intervals between 8:00 and 18:00 over 22 days. For the estimation of GHG emissions, climatic data measured through a meteorological station were used, in addition to environmental parameters incorporated in the CDC. Five RNN models composed of two hidden layers of 20, 25, and 50 neurons were developed, trained, and validated for each GHG. Results indicate that N₂O contributed most to total emissions (734,689 ppm CO₂-eq), with CO₂ (237,579 ppm CO₂-eq) and CH₄ (215,426 ppm CO₂-eq) contributing less. Model performance was strong, with R² values of 0.98 (CO₂), 0.96 (N₂O), and 0.94 (CH₄). It is concluded that the RNNs proved to be reliable models for predicting GHG emissions in unfertilized coffee soils, with this study presenting a replicable framework with the potential to improve temporal estimation and reduce uncertainty in GHG inventories.

Downloads

Published

How to Cite

Issue

Section

License

Copyright (c) 2025 Author(s)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

References

1. Pinto Taborga C. A methodology and a mathematical model for reducing greenhouse gas emissions through the supply chain redesign [PhD thesis]. Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya; 2018.

2. Maqueda González MR, Carbonell Padrino MV, MartínezRamírez E, Flórez García M. Sources of greenhouse gas emissions in agriculture (Spanish). Ingeniería de Recursos Naturales y del Ambiente. 2005; (4): 14–18.

3. Benaouda M, Martin C, Li X, et al. Evaluation of the performance of existing mathematical models predicting enteric methane emissions from ruminants: Animal categories and dietary mitigation strategies. Animal Feed Science and Technology. 2019; 255: 114207. doi: 10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2019.114207 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2019.114207

4. Pachauri RK, Allen MR, Barros VR, et al. Climate change 2014: synthesis report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II, and III to the fifth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. IPCC; 2014.

5. Sanucci C. Evaluation of methane levels in oil production areas using satellite imagery under a data science approach (Spanish) [PhD thesis]. Universidad Nacional de La Plata; 2021.

6. Ramos Díaz JI. Determination of methane emissions in an activated sludge wastewater treatment plant (Spanish) [Master’s thesis]. Tesis (MC)--Centro de Investigación y de Estudios Avanzados del IPN Departamento de Biotecnología y Bioingeniería; 2022.

7. Sánchez Ureña SG. Characterization of methanotrophic activity in lakes by laser spectrometry (Spanish) [Master’s thesis]. Centro de Investigación y de Estudios Avanzados del IPN Departamento de Biotecnología y Bioingeniería; 2015

8. Xu Z, Chen Y, Cai X. Can green electrification expansion to rice cultivation reduce agricultural methane emissions in China?. Journal of Cleaner Production. 2024; 434: 139906. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.139906 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.139906

9. Houghton JT, Ding YDJG, Griggs DJ, et al. Climate change 2001: the scientific basis: contribution of Working Group I to the third assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press; 2001

10. Amon B, Amon T, Boxberger J, et al. Emissions of NH3, N2O, and CH4 from dairy cows housed in a farmyard manure tying stall (housing, manure storage, manure spreading). Nutrient cycling in Agroecosystems. 2001; 60(1): 103-113. doi: 10.1023/A:1012649028772 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1012649028772

11. Baethgen W, Martino D. Climate change, greenhouse gases and implications for the agricultural and forestry sectors of Uruguay (Spanish). Resúmenes del Taller sobre el Protocolo de Kyoto. Ministerio de Vivienda, ordenamiento territorial y Medio Ambiente. Dirección Nacional de Medio Ambiente. Uruguay, 2000.

12. Capurro MC, Tarlera S, Irisarri P, et al. Quantification of methane and nitrous oxide emissions under two contrasting irrigation management practices in rice cultivation (Spanish). Montevideo: INIA (INIA Serie Técnica. 2015; 220: 38.

13. Chen Y, Guo W, Ngo HH, et al. Ways to mitigate greenhouse gas production from rice cultivation. Journal of Environmental Management. 2024; 368: 122139. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2024.122139 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2024.122139

14. Ryan EM, Ogle K, Kropp H, et al. Modeling soil CO2 production and transport with dynamic source and diffusion terms: testing the steady-state assumption using DETECT v1. 0. Geoscientific Model Development. 2018; 11(5): 1909-1928. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-11-1909-2018

15. Biosciences L. Using the LI-8100A Soil Gas Flux System & the LI-8150 Multiplexer. Lincoln, Nebraska, USA, 2015.

16. Huttunen JT, Alm J, Liikanen A, et al. Fluxes of methane, carbon dioxide, and nitrous oxide in boreal lakes and potential anthropogenic effects on the aquatic greenhouse gas emissions. Chemosphere. 2003; 52(3): 609-621. doi: 10.1016/S0045-6535(03)00243-1 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0045-6535(03)00243-1

17. Johansson AE, Gustavsson AM, Öquist MG, et al. Methane emissions from a constructed wetland treating wastewater—seasonal and spatial distribution and dependence on edaphic factors. Water research. 2004; 38(18): 3960-3970. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2004.07.008 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2004.07.008

18. Singh VP, Dass P, Kaur K, et al. Nitrous oxide fluxes in a tropical shallow urban pond under influencing factors. Current science. 2005; 478-483.

19. Lambert M, Fréchette JL. Analytical techniques for measuring fluxes of CO2 and CH4 from hydroelectric reservoirs and natural water bodies. In: Greenhouse gas emissions—fluxes and processes: hydroelectric reservoirs and natural environments. Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2005. pp. 37-60. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-26643-3_3 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-26643-3_3

20. Stadmark J, Leonardson L. Emissions of greenhouse gases from ponds constructed for nitrogen removal. Ecological Engineering. 2005; 25(5): 542-551. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoleng.2005.07.004 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoleng.2005.07.004

21. Sovik AK, Augustin J, Heikkinen K, et al. Emission of the greenhouse gases nitrous oxide and methane from constructed wetlands in Europe. Journal of environmental quality. 2006; 35(6): 2360-2373. doi: 10.2134/jeq2006.0038 DOI: https://doi.org/10.2134/jeq2006.0038

22. Yacob S, Hassan MA, Shirai Y, et al. Baseline study of methane emission from anaerobic ponds of palm oil mill effluent treatment. Science of the total environment. 2006; 366(1): 187-196. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2005.07.003 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2005.07.003

23. Sovik AK, Kløve B. N₂O and CH₄ emissions from an artificial wetland in southeastern Norway (Spanish). Science of The Total Environment. 2007; 380(1): 28–37.doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2006.10.007 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2006.10.007

24. Mander Ü, Lõhmus K, Teiter S, et al. Gaseous fluxes in the nitrogen and carbon budgets of subsurface flow constructed wetlands. Science of the Total Environment. 2008; 404(2-3): 343-353. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2008.03.014 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2008.03.014

25. Barton L, Wolf B, Rowlings D, et al. Sampling frequency affects estimates of annual nitrous oxide fluxes. Scientific reports. 2015; 5(1): 15912. doi: 10.1038/srep15912 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep15912

26. Reeves S, Wang W, Salter B, et al. Quantifying nitrous oxide emissions from sugarcane cropping systems: Optimum sampling time and frequency. Atmospheric Environment. 2016; 136: 123-133. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2016.04.008 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2016.04.008

27. Grace PR, van der Weerden TJ, Rowlings DW, et al. Global Research Alliance N2O chamber methodology guidelines: Considerations for automated flux measurement. Journal of Environmental Quality. 2020; 49(5): 1126-1140. doi: 10.1002/jeq2.20124 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/jeq2.20124

28. Ait Issad H, Aoudjit R, Rodrigues JJPC. A comprehensive review of Data Mining techniques in smart agriculture. Engineering in Agriculture, Environment, and Food. 2019; 12(4): 511-525. doi: 10.1016/j.eaef.2019.11.003 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eaef.2019.11.003

29. Cueva-Rodríguez A, Yépez EA, Garatuza-Payán J, et al. Diseño y uso de un sistema portátil para medir la respiración de suelo en ecosistemas. Terra Latinoamericana. 2012; 30(4): 327-336.

30. Robles N. Sostenibilidad de la Cadena de Suministros mediante el Control de las Emisiones de Gases de Efecto Invernadero. In: Proceedings of the 15th LACCEI International Multi-Conference for Engineering, Education and Technology; 19–21 July 2017; Boca Raton – Florida, United States. doi: 10.18687/LACCEI2017.1.1.304 DOI: https://doi.org/10.18687/LACCEI2017.1.1.304

31. Teloxa LCL, Rivas AIM, Gómez-Díaz JD. Calibration design to quantify CO2 emissions (soil respiration) during daytime intervals (Spanish). Agrociencia. 2020; 54(6): 747-761. doi: 10.47163/agrociencia.v54i6.2188 DOI: https://doi.org/10.47163/agrociencia.v54i6.2188

32. Peralta Zuñiga K. Greenhouse gas emissions and soil carbon and nitrogen dynamics in coffee crops (Spanish) [Master’s thesis]. Agriculture and Rural Development (SADER); 2021.

33. Merkel A. Climate of Chirinos (Peru) (Spanish). Available online: https://es.climate-data.org/search/?q=chirinos (accessed on 27 June 2024).

34. SENAHMI. SENAMHI - Climate Map of Peru (Spanish). Available online: https://www.senamhi.gob.pe/?p=mapa-climatico-del-peru (accessed on 27 June 2024).

35. INRENA. Soil map of Peru: 1:5,000,000 (Spanish). Available online: https://pesquisa.bvsalud.org/portal/resource/pt/des-16920 (accessed on 27 June 2024).

36. Khumaidi A. Data mining for predicting the amount of coffee production using crisp-dm method. Jurnal Techno Nusa Mandiri. 2020; 17(1): 1-8. DOI: https://doi.org/10.33480/techno.v17i1.1240

37. González RR, Llaugel FA. A predictive model of school dropout for the Dominican Republic (Spanish). Revie-Revista de Investigación y Evaluación Educativa. 2016; 3(1): 42-65. doi: 10.47554/revie.vol3.num1.2016.pp42-65 DOI: https://doi.org/10.47554/revie.vol3.num1.2016.pp42-65

38. Okoye K, Nganji JT, Escamilla J, et al. Machine learning model (RG-DMML) and ensemble algorithm for prediction of students’ retention and graduation in education. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence. 2024; 6: 100205. doi: 10.1016/j.caeai.2024.100205 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeai.2024.100205

39. Zeinalnezhad M, Shishehchi S. An integrated data mining algorithms and meta-heuristic technique to predict the readmission risk of diabetic patients. Healthcare Analytics. 2024; 5: 100292. doi: 10.1016/j.health.2023.100292 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.health.2023.100292

40. Valdiviezo ROM, Gorozabel OAL, Indio JAA, et al. Mechanisms for big data processing. Data cleaning, transformation, and analysis (Spanish). Polo del Conocimiento. 2023; 8(4): 656-675. doi: 10.23857/pc.v8i4.5457

41. Fisher RA. Statistical methods for research workers, 11th ed. Oliver and Boyd; 1925.

42. Willmott CJ, Matsuura K. Advantages of the mean absolute error (MAE) over the root mean square error (RMSE) in assessing average model performance. Climate research. 2005; 30(1): 79-82. doi: 10.3354/cr030079 DOI: https://doi.org/10.3354/cr030079

43. Hyndman RJ, Koehler AB. Another look at measures of forecast accuracy. International journal of forecasting. 2006; 22(4): 679-688. doi: 10.1016/j.ijforecast.2006.03.001 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijforecast.2006.03.001

44. Paccha J, Alvarado V, Heidinger H, et al. Measurement of greenhouse gases in agricultural and livestock soils using closed static chambers in the Zalapa sector, city of Loja (Spanish). Bosques Latitud Cero. 2024; 14(1): 137-149. doi: 10.54753/blc.v14i1.2129 DOI: https://doi.org/10.54753/blc.v14i1.2129

45. Montenegro-Ballestero J. Polynomial response to nitrous oxide emissions in coffee plantations in Costa Rica (Spanish). Revista de Ciencias Ambientales. 2019; 53(2): 1-24. doi: 10.15359/rca.53-2.1 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15359/rca.53-2.1

46. Li B, Gu W, Zhao Y, et al. Differentiated strategies for synergistic mitigation of ammonia and methane emissions from agricultural cropping systems in China. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology. 2024; 358: 110250. doi: 10.1016/j.agrformet.2024.110250 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet.2024.110250

47. Pastrana JL, Allen JL, Becket E, et al. Interactions between nitrogen and carbon availability and carbon quality on soil microbial abundance and activity in semi-arid shrubland soils. Applied Soil Ecology. 2025; 214: 106360. doi: 10.1016/j.apsoil.2025.106360 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsoil.2025.106360

48. Lin X, Schneider RL, Morreale SJ, et al. The impacts of shrub branch shelter and nitrogen addition on soil microbial activity and plant litter decomposition in a desert steppe. Applied Soil Ecology. 2025; 207: 105956. doi: 10.1016/j.apsoil.2025.105956 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsoil.2025.105956

49. Waqas MA, Li Y, Ashraf MN, et al. Long-term warming and elevated CO2 increase ammonia-oxidizing microbial communities and accelerate nitrification in paddy soil. Applied Soil Ecology. 2021; 166: 104063. doi: 10.1016/j.apsoil.2021.104063 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsoil.2021.104063

50. Wang Z, Xiao S, Reuben C, et al. Soil NOx Emission Prediction via Recurrent Neural Networks. Computers, Materials & Continua. 2023; 77(1). doi: 10.32604/cmc.2023.044366 DOI: https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2023.044366

51. Castillo-Girones S, Munera S, Martínez-Sober M, et al. Artificial Neural Networks in Agriculture, the core of artificial intelligence: What, When, and Why. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture. 2025; 230: 109938. doi: 10.1016/j.compag.2025.109938 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2025.109938

52. Dey A, Ashok SD. Trustworthy and Human Centric neural network approaches for prediction of landfill methane emission and sustainable waste management practices. Waste Management. 2025; 195: 44-54. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2025.01.017 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2025.01.017

53. Noponen MRA, Edwards-Jones G, Haggar JP, et al. Greenhouse gas emissions in coffee grown with differing input levels under conventional and organic management. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment. 2012; 151: 6-15. doi: 10.1016/j.agee.2012.01.019 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2012.01.019

54. Hosny KM, El-Hady WM, Samy FM. Technologies, Protocols, and applications of Internet of Things in greenhouse Farming: A survey of recent advances. Information Processing in Agriculture. 2025; 12(1): 91-111. doi: 10.1016/j.inpa.2024.04.002 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inpa.2024.04.002

55. Kong X, Wang L, Yu W, et al. Impact of inlet CO2 on the performance of AEMFCs: Mechanistic insights and mitigation strategies. Clean Energy Science and Technology. 2025; 3(3): 369. doi: 10.18686/cest369 DOI: https://doi.org/10.18686/cest369

56. Dupuis A, Dadouchi C, Agard B. Methodology for multi-temporal prediction of crop rotations using recurrent neural networks. Smart Agricultural Technology. 2023; 4: 100152. doi: 10.1016/j.atech.2022.100152 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atech.2022.100152

.jpg)

.jpg)