Research on screening strategy of Organic Rankine Cycle working fluids based on quantum chemistry

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.18686/cest.v2i2.169Keywords:

Organic Rankine cycle; selection of working fluids; RCF; thermodynamicsAbstract

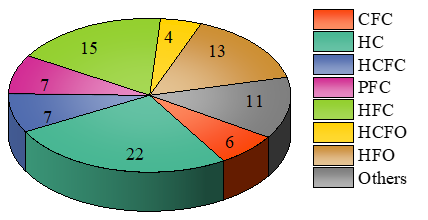

The screening of working fluids is one of the key components in the study of power generation systems utilizing low-temperature waste heat. However, the variety of working fluids and their complex composition increase the difficulty of screening working fluids. In this study, a screening strategy for working fluids was developed from the perspective of the thermodynamic physical properties of working fluids. A comparative ideal gas heat capacity via the reduced ideal gas heat capacity factor (RCF) was proposed to characterize the dry and wet properties of working fluids, where RCF > 1 indicated a dry working fluid and RCF < 1 indicated a wet working fluid. A three-step screening strategy was developed for working fluid screening for organic Rankine cycles (ORCs). The strategy comprised basic physical property analysis of working fluids, research on dry and wet properties, and quantum chemical analysis. By comparing the RCF calculation result of 23 selected working fluid with values from the literature, the relative deviations of the data were less than 6.64% overall, indicating that the calculation result of the RCFs is reliable. The selection strategy explains the mechanism of working fluid selection in ORC systems from both micro- and macro-perspectives, laying a foundation for the study of structure-activity relationships in working fluids for ORCs.

Downloads

Published

How to Cite

Issue

Section

License

Copyright (c) 2024 Yi Wang, Jiawen Yang, Li Xia, Xiaoyan Sun, Shuguang Xiang, Lili Wang

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

References

1. Sun R, Yang K, Wang B, et al. Technical and economic optimization of low-temperature waste heat recovery for supercritical carbon dioxide coal-fired power generation systems (Chinese). Thermal Power Generation. 2020; 010: 049.

2. Zhang C. Comprehensive Performance Evaluation and Experimental Study of Low-Grade Waste Heat Organic Rankine Cycle (Chinese) [PhD thesis]. Chongqing University; 2018.

3. Rowlands IH. The Fourth Meeting of the Parties to the Montreal Protocol: Report and Reflection. Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development. 1993, 35(6): 25-34. doi: 10.1080/00139157.1993.9929109 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/00139157.1993.9929109

4. Bao J, Zhao L. A review of working fluid and expander selections for organic Rankine cycle. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 2013, 24: 325-342. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2013.03.040 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2013.03.040

5. Martin TM, Young DM. Prediction of the Acute Toxicity (96-h LC50) of Organic Compounds to the Fathead Minnow (Pimephales promelas) Using a Group Contribution Method. Chemical Research in Toxicology. 2001, 14(10): 1378-1385. doi: 10.1021/tx0155045 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1021/tx0155045

6. Kondo S, Urano Y, Tokuhashi K, et al. Prediction of flammability of gases by using F-number analysis. Journal of Hazardous Materials. 2001, 82(2): 113-128. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3894(00)00358-7 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3894(00)00358-7

7. Zhang X, Zhang Y, Wang J. New classification of dry and isentropic working fluids and a method used to determine their optimal or worst condensation temperature used in Organic Rankine Cycle. Energy. 2020, 201: 117722. doi: 10.1016/j.energy.2020.117722 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2020.117722

8. Zhang T, Liu L, Hao J, et al. Correlation analysis based multi-parameter optimization of the organic Rankine cycle for medium- and high-temperature waste heat recovery. Applied Thermal Engineering. 2021, 188: 116626. doi: 10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2021.116626 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2021.116626

9. Groniewsky A, Györke G, Imre AR. Description of wet-to-dry transition in model ORC working fluids. Applied Thermal Engineering. 2017, 125: 963-971. doi: 10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2017.07.074 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2017.07.074

10. Garrido JM, Quinteros-Lama H, Mejía A, et al. A rigorous approach for predicting the slope and curvature of the temperature–entropy saturation boundary of pure fluids. Energy. 2012, 45(1): 888-899. doi: 10.1016/j.energy.2012.06.073 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2012.06.073

11. Lukawski MZ, Tester JW, DiPippo R. Impact of molecular structure of working fluids on performance of organic Rankine cycles (ORCs). Sustainable Energy & Fuels. 2017, 1(5): 1098-1111. doi: 10.1039/c6se00064a DOI: https://doi.org/10.1039/C6SE00064A

12. Wang J, Zhang J, Chen Z. Molecular Entropy, Thermal Efficiency, and Designing of Working Fluids for Organic Rankine Cycles. International Journal of Thermophysics. 2012, 33(6): 970-985. doi: 10.1007/s10765-012-1200-6 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10765-012-1200-6

13. Stijepovic MZ, Linke P, Papadopoulos AI, et al. On the role of working fluid properties in Organic Rankine Cycle performance. Applied Thermal Engineering. 2012, 36: 406-413. doi: 10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2011.10.057 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2011.10.057

14. Palma-Flores O, Flores-Tlacuahuac A, Canseco-Melchorb G. Simultaneous molecular and process design for waste heat recovery. Energy. 2016, 99: 32-47. doi: 10.1016/j.energy.2016.01.024 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2016.01.024

15. Papadopoulos AI, Stijepovic M, Linke P. On the systematic design and selection of optimal working fluids for Organic Rankine Cycles. Applied Thermal Engineering. 2010, 30(6-7): 760-769. doi: 10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2009.12.006 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2009.12.006

16. Ingman VM, Schaefer AJ, Andreola LR, et al. QChASM: Quantum chemistry automation and structure manipulation. WIREs Computational Molecular Science. 2020, 11(4). doi: 10.1002/wcms.1510 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/wcms.1510

17. Bogojeski M, Vogt-Maranto L, Tuckerman ME, et al. Quantum chemical accuracy from density functional approximations via machine learning. Nature Communications. 2020, 11(1). doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19093-1 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-19093-1

18. Needham CD, Westmoreland PR. Combustion and flammability chemistry for the refrigerant HFO-1234yf (2,3,3,3-tetrafluroropropene). Combustion and Flame. 2017, 184: 176-185. doi: 10.1016/j.combustflame.2017.06.004 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.combustflame.2017.06.004

19. Chen H, Goswami DY, Stefanakos EK. A review of thermodynamic cycles and working fluids for the conversion of low-grade heat. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 2010, 14(9): 3059-3067. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2010.07.006 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2010.07.006

20. Liu BT, Chien KH, Wang CC. Effect of working fluids on organic Rankine cycle for waste heat recovery. Energy. 2004, 29(8): 1207-1217. doi: 10.1016/j.energy.2004.01.004 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2004.01.004

21. Poling BE, Prausnitz JM, O’Connell JP. Properties of Gases and Liquids, 5th ed. McGraw-Hill Education; 2001.

22. Linderberg J, Öhrn Y, Brändas EJ, et al. Per-Olov Löwdin. Löwdin Volume. Published online 2017: 1-7. doi: 10.1016/bs.aiq.2016.04.001 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.aiq.2016.04.001

23. Boeyens JCA. Quantum Chemistry. The Theories of Chemistry. Published online 2003: 261-332. doi: 10.1016/b978-044451491-2/50018-7 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-044451491-2/50018-7

24. Tu W, Bai L, Zeng S, et al. An ionic fragments contribution-COSMO method to predict the surface charge density profiles of ionic liquids. Journal of Molecular Liquids. 2019, 282: 292-302. doi: 10.1016/j.molliq.2019.03.004 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2019.03.004

25. Grensemann H, Gmehling J. Performance of a Conductor-Like Screening Model for Real Solvents Model in Comparison to Classical Group Contribution Methods. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research. 2005, 44(5): 1610-1624. doi: 10.1021/ie049139z DOI: https://doi.org/10.1021/ie049139z

26. Johnson ER, Keinan S, Mori-Sánchez P, et al. Revealing Noncovalent Interactions. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2010, 132(18): 6498-6506. doi: 10.1021/ja100936w DOI: https://doi.org/10.1021/ja100936w

27. Lu T, Chen F. Multiwfn: A multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. Journal of Computational Chemistry. 2011, 33(5): 580-592. doi: 10.1002/jcc.22885 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/jcc.22885

28. Wu W, Yang Y, Wang B, et al. The effect of the degree of substitution on the solubility of cellulose acetoacetates in water: A molecular dynamics simulation and density functional theory study. Carbohydrate Research. 2020, 496: 108134. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2020.108134 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carres.2020.108134

29. Lukawski MZ, DiPippo R, Tester JW. Molecular property methods for assessing efficiency of organic Rankine cycles. Energy. 2018, 142: 108-120. doi: 10.1016/j.energy.2017.09.140 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2017.09.140

30. Emamian S, Lu T, Kruse H, et al. Exploring Nature and Predicting Strength of Hydrogen Bonds: A Correlation Analysis Between Atoms‐in‐Molecules Descriptors, Binding Energies, and Energy Components of Symmetry‐Adapted Perturbation Theory. Journal of Computational Chemistry. 2019, 40(32): 2868-2881. doi: 10.1002/jcc.26068 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/jcc.26068

31. Li G, Gui C, Dai C, et al. Molecular Insights into SO2 Absorption by [EMIM][Cl]-Based Deep Eutectic Solvents. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering. 2021, 9(41): 13831-13841. doi: 10.1021/acssuschemeng.1c04639 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1021/acssuschemeng.1c04639

32. Klamt A. COSMO-RS: From Quantum Chemistry to Fluid Phase Thermodynamics and Drug Design. Elsevier; 2005.

33. AL-Arfi I, Shboul B, Poggio D, et al. Thermo-economic and design analysis of a solar thermal power combined with anaerobic biogas for the air gap membrane distillation process. Energy Conversion and Management. 2022; 257: 115407. doi: 10.1016/j.enconman.2022.115407 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2022.115407

.jpg)

.jpg)